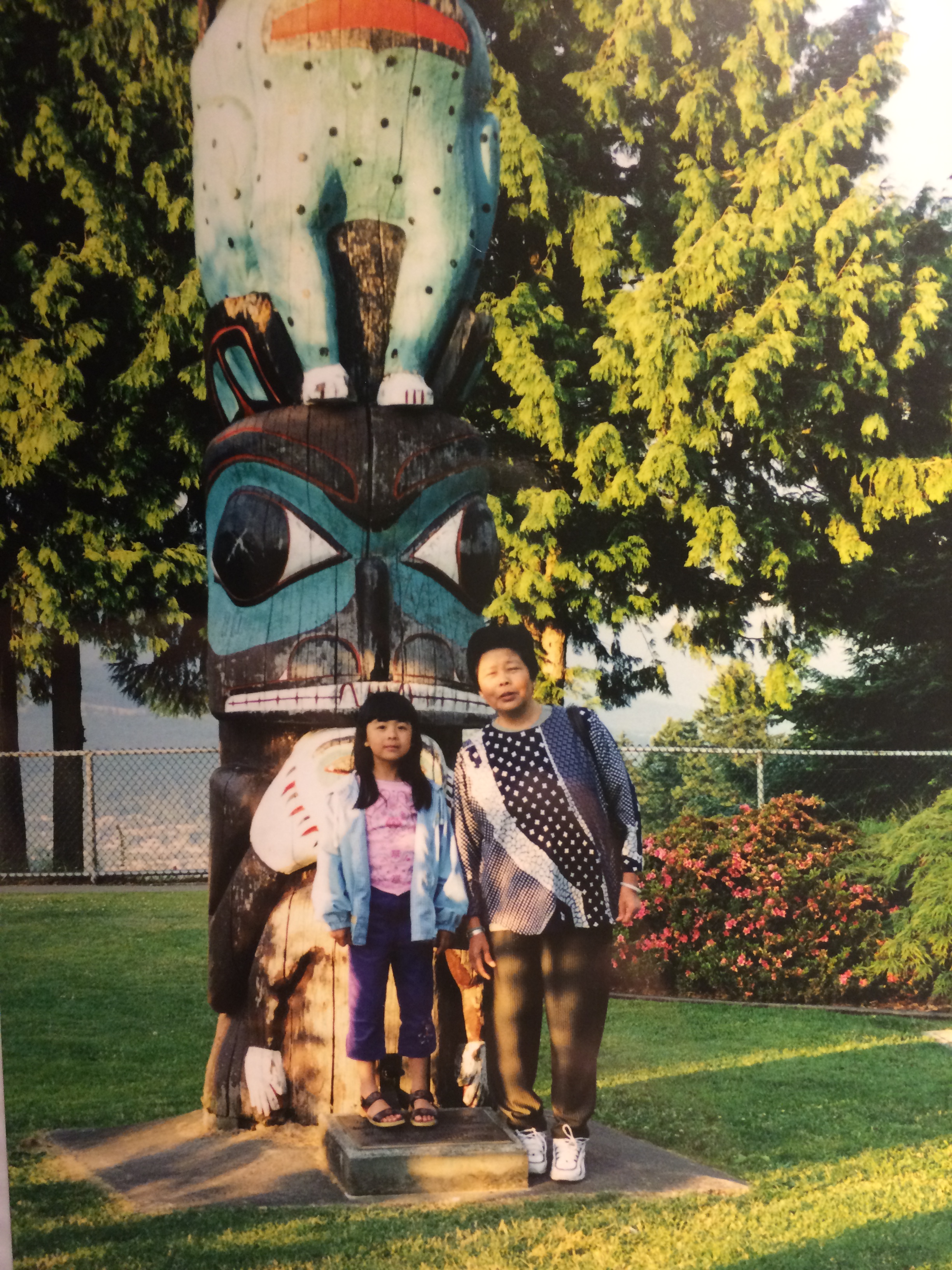

I wrote about my poh-poh (grandmother) here.

I have been away from home.

That evening, I thought of calling my poh-poh.

I have not set foot in the motherland in nine years.

I am Chinese diaspora. We left before my brain was capable of remembering. My memories of the motherland used to be an outdated globe that still showed Russia as the U.S.S.R. In my make-believe childhood memories, Hong Kong is a courtyard. Pastel sunlight and beige stone bricks on the ground. It is blisteringly hot. A pagoda. And a man wearing dark pants and a blue collared shirt. There are no sounds in this memory. I will never know where this image comes from. But in my childish memories, I imagine all of Hong Kong and China like this. Even after I learned how to use Google, the motherland is a courtyard with a man in a blue shirt.

I am transnational with no memories. No smells, no sounds.

I am an uninvited guest. Settler. Immigrant. One who never dreams in her language.

There is nothing to say to Poh-poh.

What a betrayal it must be to forget the first language you ever learned. I must have heard my language in the womb. This was our tongue before English.

When I am surrounded by Cantonese, I feel home. My brain, like leaves as the sun comes up, begins to unfurl. And then, at the moment when I must participate, I am reminded of how shaky, how contentious, this ground that I dare to call home is. This feeling I called home feels suffocating in my body.

Yesterday, my mother told me that her uncle had left at last. I cannot estimate how long we had been holding his cancer on our breaths. Perhaps I forgot.

She told me as if she had already told me, but I don’t think she did. Maybe I had forgotten. I didn’t tell her that I was surprised. I pretended that I already knew.

We have talked about this before, but she tells me again. Everyone is born. They age. People get sick. And we die.

My mother’s uncle had been preparing to die for a long time. He had been ready and he had been trying to ensure that the people he loved would be ready too. He is returning to his village in Guangdong province to be with his parents. Going home.

When I hang up the phone, I look up the province, to see the shape against the outline of the rooster. I search for the proper title for my mother’s father’s younger brother.

In my head and quietly under my breath, I rehearse how I will tell Poh-poh that I am sorry; I can only be here. My mother told me to be good. Be good in this moment.